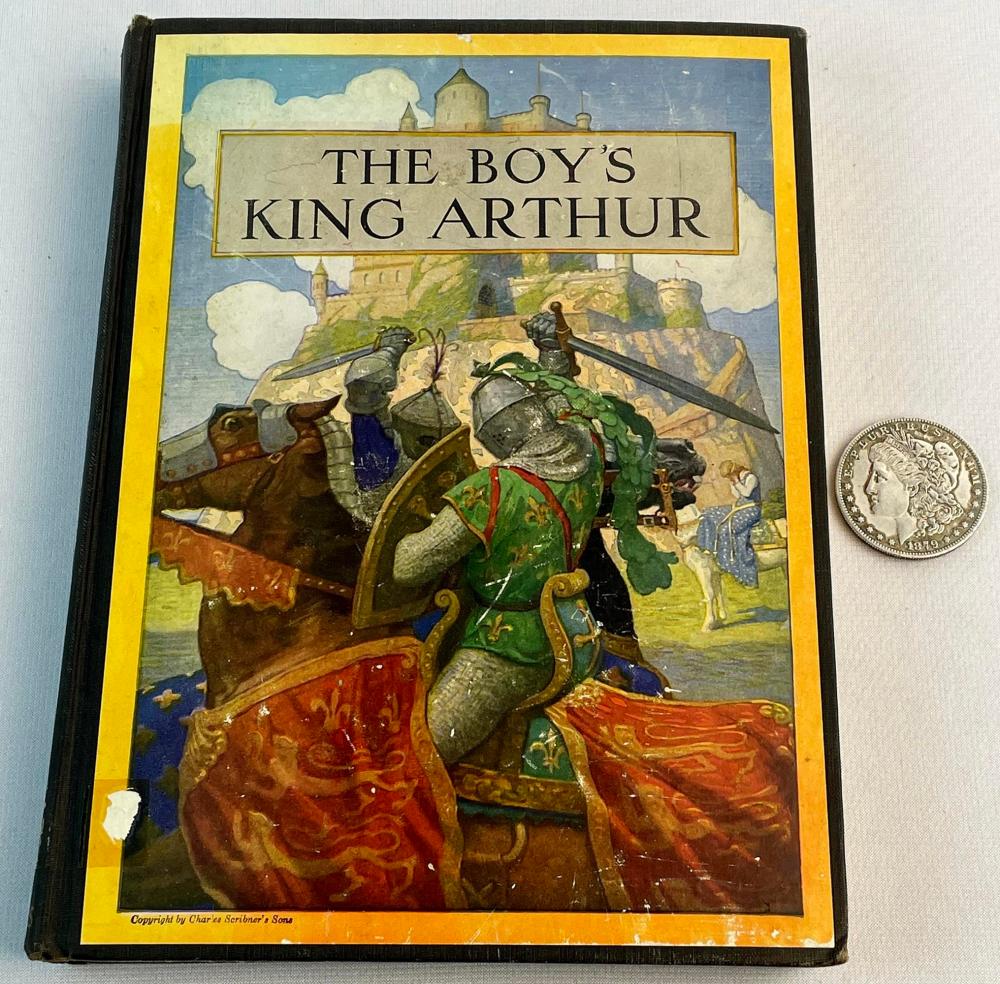

"The Boy's King Arthur" Lot no. 3923

By N.C. Wyeth 1882-1945

1917

39.25" x 31.25", Framed 46.75" x 38.75"

Oil on Canvas

Signed Lower Right: Wyeth

SOLD

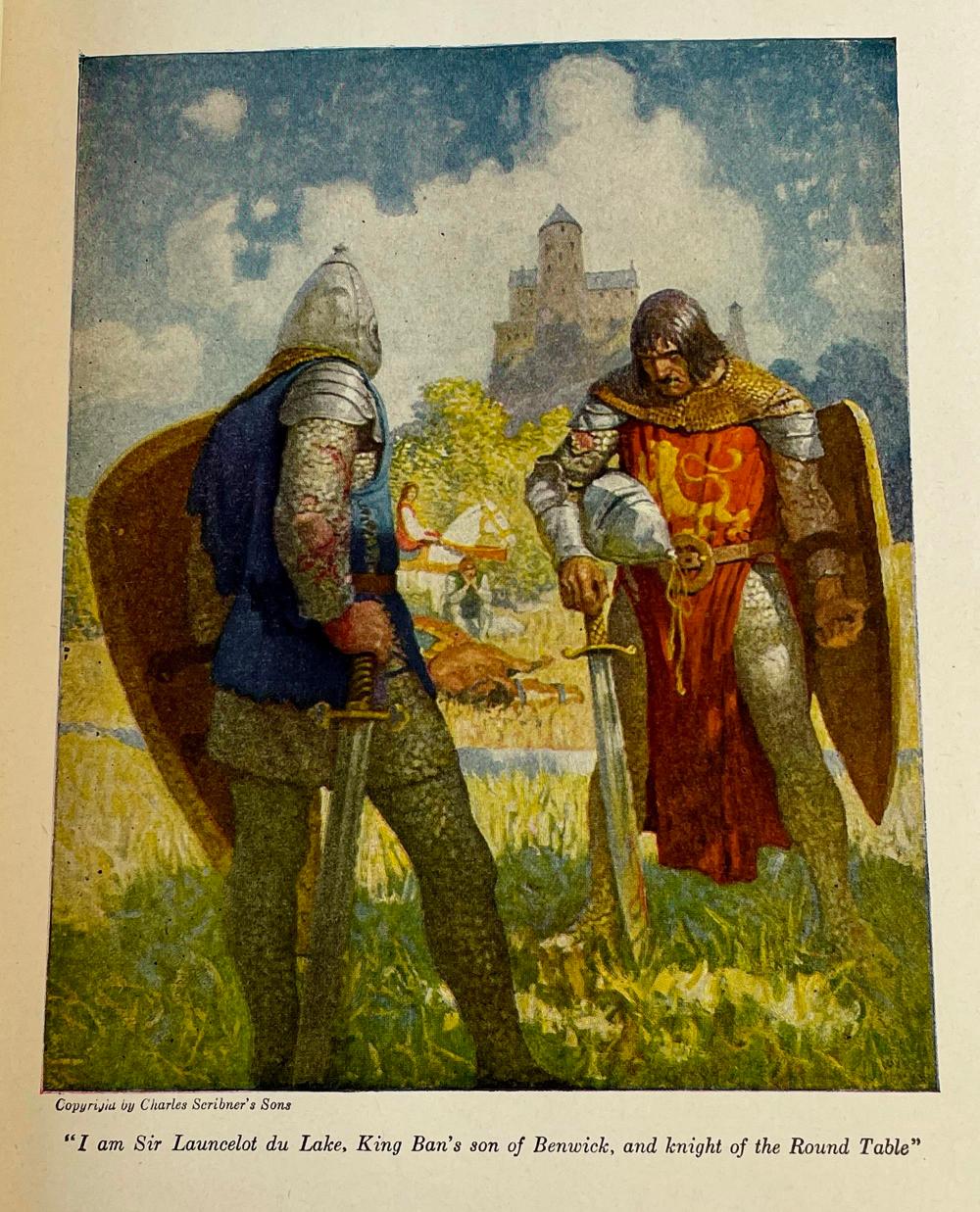

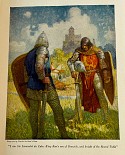

"I am Sir Launcelot du Lake, King Ban's son of Benwick, and knight of the Round Table," The Boy's King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table interior book illustration, 1917

Although N. C. Wyeth achieved immediate commercial success with his early depictions of cowboys, pioneers, and Native Americans from the Old West, by the 1910s, he began imaging medieval tales of romance and adventure, further broadening his audience-and popularity. His 1916 illustrations for Robert Louis Stevenson's The Black Arrow: A Tale of the Two Roses and Mark Twain's "The Mysterious Stranger" conjured up thrilling new worlds of armored knights, damsels in distress, and spell-casting wizards. In 1917 he conceived of 17 works, including the present magnificent lot, for the latest edition of Sidney Lanier's The Boy's King Arthur. The illustrated version became an instant children's classic and led to art commissions for other stories set in the Middle Ages, such as Paul Creswick's Robin Hood (1917), Arthur Conan Doyle's The White Company (1922), and Thomas Bulfinch's Legends of Charlemagne (1924).

In 1880, Southern author and editor Sidney Lanier debuted The Boy's King Arthur, a condensed version of Sir Thomas Malory's 1485 Le Morte d'Arthur. Organized into seven chapters, The Boy's King Arthur highlights the major episodes in the chronicles of the legendary fifth-century British King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Wyeth's 17 illustrations for the 1917 edition of the book attracted a whole new generation of King Arthur fans. Each scene reveals Wyeth's penchant for historical details, rich palette (anchored by blues and golds), and theatrical lighting, as well as his facility in rendering the human body in motion. Most important for a reader, the illustrations capture the climactic turning point of each chapter, just before the denouement: for example, Arthur sailing up to the sword Excalibur magically emerging from the sea; King Mark raising his sword to kill Sir Tristram, playing the lyre unawares next to his lover, Isolde; or Sir Launcelot fleeing with Queen Guinevere on horseback after their affair has come to light.

The present lot is one of two illustrations from Chapter 2, which tells the story of the greatest of King Arthur's knights, Sir Launcelot du Lake. In an effort to impress Queen Guinevere, Launcelot sets off into the forest seeking adventure and encounters a damsel riding on a white horse. The damsel describes an evil, powerful knight, Sir Turquine, who wreaks havoc throughout the land and who has imprisoned in his nearby castle 64 knights and ladies. As if on cue, Turquine appears in the distance, effortlessly subduing another knight from the Round Table, Sir Gaheris. Launcelot rides up to the men and challenges Turquine to fight him instead, whereupon a vicious, equally matched brawl ensues: their horses' backs break and must continue their combat on foot. After hours of "feinting and thrusting" swords and "passing blood grievously," the men pause, and Turquine proposes a truce: he will release the prisoners from his castle as long as his foe reveals his name and is NOT Launcelot, who killed Turquine's brother, Sir Carados (S. Lanier, The Boy's King Arthur, New York, 1929, p. 37). For the illustration, Wyeth depicts the pivotal moment at which Launcelot, in blue, speaks the only words that will enrage Turquine, in red: "I AM Sir Launcelot du Lake, King Ban's son of Benwick, and knight of the Round Table" (Lanier, p. 38). Realizing a truce is impossible because of his identity, the "unmasked" Launcelot pounces like a lion on Turquine and beheads him.

I am Sir Launcelot du Lake exhibits the major art tenets that Wyeth learned at Howard Pyle's famous School of Art in Wilmington, Delaware. Pyle insisted that his students empathize with their subjects so that they could convincingly portray the "the emotions, the thoughts, the actions of . . . fellow men" (C. Podmaniczky, N.C. Wyeth: Catalogue Raisonne of Paintings, Volume I, London, 2008, p. 22). Wyeth took this lesson to heart when selecting his book commissions: "In the first reading, he sought a crucial spark of sympathetic engagement. . . . During a second reading, [he] noted the historical facts and the development of the main characters. More importantly, he considered other significant and valuable elements . . . such as 'telling backgrounds and moods'" (Podmaniczky, p. 27). For the present illustration, Wyeth positions Launcelot with his back to the picture plane so that the reader-viewer steps into his armor, feeling both his bloodied elbow and powerful stature. Wyeth likewise captures the complexity of Turquine's persona, his muscled physique, hunched-over shoulders signaling exhaustion, and his expression of hatred. Background details further amplify the tense atmosphere: Launcelot's slain horse littering the field; Sir Gaheris, defeated by Turquine, sitting dejected with his hands bound; astride her white horse, the damsel scout nervously watching the fight; and on top of the hill, Turquine's shadowed castle, in whose dungeon 64 lives are at stake.

Teacher Pyle also encouraged his students to employ historical authenticity in their narrative scenes, and toward that end, Wyeth began frequenting museums and historical societies, building his own library, and collecting or renting period props and costumes, what Pyle called "properties." The art historian Stanley Grand points out that in the present lot, Wyeth references the Middle Ages, when King Arthur literature flourished, rather than the late fifth century, when he actually reigned: "Turquine's helmet with its pointed, 'sugar loaf' crown, for example, more closely dates to the 13th century, and Launcelot's with its greater visibility is even later. Although both warriors wear mail hauberks (mail shirts with sleeves that reach to mid-thigh) and chausses (mail armor 'socks' covering the legs), the additional plate armor pauldrons to protect the shoulders are not consistent with the earlier period. In sum, although creating the illusion of historical accuracy, the armor is really a pastiche evoking the era when King Arthur appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's 12th-century Historia Regum Britanniae" (S.G. Grand, Selections from the Sordoni Collection: American Illustration & Comic Art, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, 2018, p. 78).

According to Pyle, in addition to rendering characters and settings as emotive and historically accurate, the artist should use technique-brushwork, palette, and tonal range-in the service of overall expression. Technically, I am Sir Launcelot du Lake shows the influence of the Italian Post-Impressionist Giovanni Segantini on Wyeth's work. After seeing an exhibition of Segantini's paintings at the Brooklyn Museum in 1913, Wyeth "heightened the brilliancy of [his] pictures 50%" and began using striated or dotted brushwork (Podmaniczky, p. 83). His illustrations for The Boy's King Arthur received acclaim for their Segantini-esque sun-drenched landscapes, rich jewel tones, and patterned surfaces, such as the speckled armor and tousled grass in I am Sir Launcelot du Lake. Here, windswept clouds and fields underscore the action of the scene; meanwhile, the vivid reds and blues of the men's tunics connote regality, while the radiant "Segantini sky" symbolizes hope for a favorable outcome for Launcelot and his fellow knights.

Shortly before his death in 1881, Sidney Lanier praised Sir Thomas Malory's 1485 Le Morte d'Arthur on which he based The Boy's King Arthur: "I suspect there are few books in our language which lead a reader-whether young or old-on from one paragraph to another with such strong and yet quiet seduction as this" (letter to Scribner, November 12, 1880). Had Lanier been alive in 1917, he would have made the exact same comment about Wyeth's extraordinary illustrations.

EXHIBITED:

Knoedler Galleries, New York, "Exhibition of Paintings by N.C. Wyeth," October 29-November 23, 1957;

Somerville Manning Gallery, Greenville, Delaware, "N.C. Wyeth," October 20-November 11, 1995;

Rossell Hope Robbins Library, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, "Visions of Courageous Achievement: Arthurian Illustration in America," 2014;

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, "Enchanted Castles and Noble Knights," November 28, 2014-January 4, 2015;

Sordoni Art Gallery, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, "Selections from the Sordoni Collection: American Illustration & Comic Art," April 7-May 20, 2018.

LITERATURE:

S. Lanier, Ed, The Boy's King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table,New York, 1972, p. 209, illustrated;

D. Allen and D. Allen, Jr., N.C. Wyeth: The Collected Paintings, Illustrations and Murals, New York, 1972, p. 209, illustrated;

J.E. Dell, Visions of Adventure: N.C. Wyeth and the Brandywine Artists, New York, 2000, p. 28. illustrated;

C.B. Podmaniczky, N.C. Wyeth: Catalogue Raisonne of Paintings, Vol. II, London, 2008, p. 345, illustrated;

Visions of Courageous Achievement: Arthurian Illustration in America, exhibition catalogue, Rochester, New York, 2014, cover and p. 9, illustrated;

J.G. Cutler and L.S. Cutler, Howard Pyle: His Students & The Golden Age of American Illustration, Newport, Rhode Island, 2017, p. 207, illustrated;

S.I. Grand, Selections from the Sordoni Collection: American Illustration & Comic Art, exhibition catalogue, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, 2018, pp. 78-79, 162, no. 36, 81, illustrated.

Explore related art collections: Magazine Stories / 1910s / Fairy Tale / $100,000 & Above

See all original artwork by N.C. Wyeth

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Newell Convers Wyeth had a huge zest for life. He carried his enthusiasm through a great number of paintings, more than 3000 illustrations, numerous vast murals, and many still-life and landscape paintings.

Howard Pyle was his teacher and idol. At first, Wyeth emulated Pyle's approach as nearly as possible, painting much of the same kind of subject matter - medieval life, pirates, Americana. To this he added his own dramatic picture concepts and rich, decorative color. Outstanding in this phase of his work were the more than twenty-five books he illustrated for Charles Scribner's Son's Classics series. The popularity of these books is such that, even after decades, many of them are still in print.

He came to resent the constraints of illustration, and after painting in oils for many years, Wyeth turned to the egg tempera medium and began to paint more for exhibitions. He also encouraged an interest in the arts in his children, giving them every opportunity for self-expression. His daughters, Henriette and Caroline, were both accomplished painters; Ann, a composer; and his son, Andrew, is famous as a painter. His grandson, Jamie, is also an excellent painter.

At the time of his tragic death in a railway crossing accident, N.C Wyeth was one of America's best loved illustrators.

The October, 1965, issue of American Heritage contains an article by Henry C. Pitz about the career of Wyeth and his family, and a biography by David Michaelis was published in 1998.