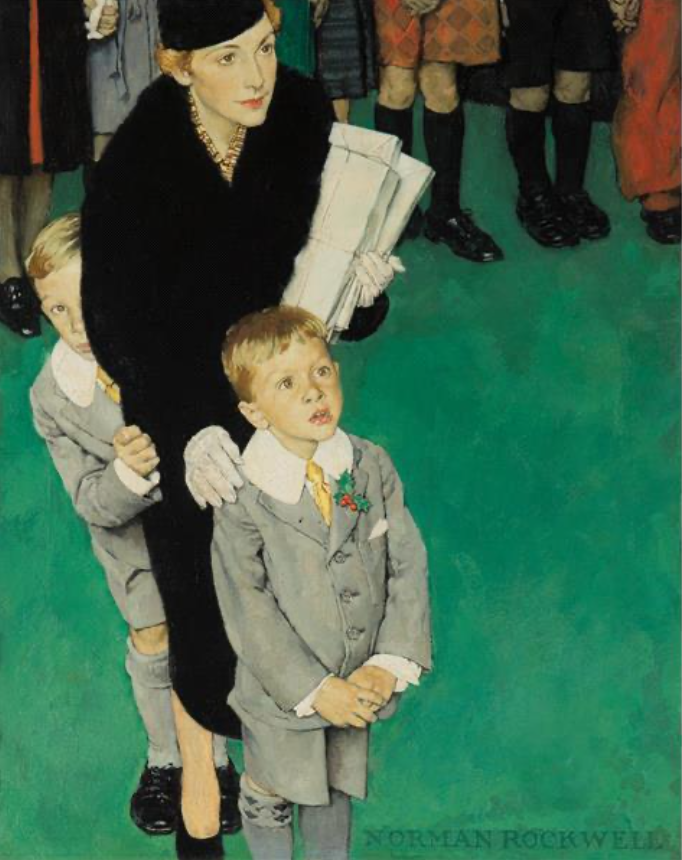

"An Audience of One" Lot no. 4314

By Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

1938

26" x 20 5/8"

Oil on Canvas

Signed Lower Right

SOLD

LITERATURE

Viola Paradise, "An Audience of One", Ladies' Home Journal, December 1938, vol. 55, no. 12, p. 20

(illustrated)

Mary Moline, Norman Rockwell Encyclopedia: A Chronological Catalog of the Artist’s Work 1910-1978, Indianapolis, 1979, fig. 2-25B, p. 100 (illustrated, p. 101)

Laurie Norton Moffatt, Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue, vol. 2, Stockbridge, 1986, no. S388, p. 687 (illustrated)

Featured in the December 1938 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, An Audience of One beautifuly displays Norman Rockwell’s ability to tell a story through a single image. First owned by fellow artist John Falter, who also painted covers for The Saturday Evening Post, and then by renowned Hollywood television producers Thomas Miller and Robert Boyett, An Audience of One has been admired by prominent storytellers for over 70 years. An Audience of One accompanied a short story in the magazine chronicling a grandfather surprising his family dressed as Santa Claus. Rockwell showcases two quintessential—yet diametrically converse—reactions to meeting such a monumental figure of childhood imagination. The young boy in front looks up in awe; the child in the back hides behind his mother, slightly afraid of meeting Santa; the woman, holding gifts, acts as a formal divide between these two opposite responses to such an iconic moment of American youth.To complement this story, Rockwell likely used his wife Mary Rhodes and two older sons Jarvis and Thomas as models for his painting. Rockwell typically used ordinary people from his community in order to tell timeless stories about childhood, the experiences that form us, and the emotions and passions that make us human. Titans of American Storytelling An Audience of One comes to auction from the formidable collection of storied television producers Thomas Miller and Robert Boyett, who found an affinity with Rockwell’s visual narrative. The legendary couple behind Miller-Boyett Productions developed some of the most influential and iconic sitcoms in television history—from Happy Days to Laverne & Shirley to Full House. The Rockwell pictures that Mr. Boyett and Mr. Miller, who died earlier this year, collected betray a compelling dialogue between three great American storytellers."In each episode of our television shows, we made sure to have characters make some form of human connection. Rockwell did the very same." — Robert Boyett Modernism and Modernity An Audience of One is also replete with myriad allusions to art history—specifically to Impressionist works. During the late 19th century, French modernism saw a new trend in which artists shifted their focus to the drama of spectatorship, replacing scenes of the opera stage in their paintings with depictions of viewers reacting to the central event. Just as Rockwell focuses on the reactions to the surprise of seeing Santa Claus, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Mary Cassatt interrogated the act of watching, each artist portraying audiences responding to what they were observing on the stage before them.An Audience of One also betrays a link with other modern modes of representation. On one hand, the immediacy of the work evokes photography’s ability to capture split-second reactions, memorializing day-to-day moments for posterity; on the other, the color-blocked construction of the painting’s subjects, outfits, and backdrop presages America’s formal push into abstraction following World War II. By approaching a subject so reflective of modernity—the excitement of seeing Santa in a major department store—through the compositional devices of the 19th and 20th century, An Audience of One captures the innovative, skillful narrative techniques of the art history’s greatest storytellers. Viola Paradise’s “An Audience of One”An Audience of One was commissioned by Ladies’ Home Journal to accompany the titular short story by Viola Paradise in which a grandfather dresses up as a fortune-telling Santa Claus in order to surprise his grandsons Nicky and Dicky and daughter-in-law Edna, and—while in character—compel her to reconcile with his son, her estranged husband. He sets up in costume where he is sure to see her, his audience of one, a spendthrift who loves getting her fortune read: her favorite department store, an aspirational site of relative luxury during the tail end of the Great Depression. After he waits two weeks for the family to finally come by, at the climax of the story—the exact moment Rockwell captured—“they came forward, Nick clinging to Edna, Dicky wide-eyed with wonder. Her eyes were searching, as if begging for some word of hope.”i In the end, the grandfather persuades Edna to reunite with her husband. Given Rockwell’s ability to condense an entire narrative into a single, concise frame, it follows naturally that many of Rockwell’s most ardent collectors are some of Hollywood’s most prominent directors, including George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—whose robust private holdings of Rockwell’s work were on view in the 2010 exhibition Telling Stories at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. The Perfect Shot"He did not just paint pictures; he told stories that implied preceding and subsequent moments in time." — Virginia MecklenburgIn An Audience of One, the artist conveys an entire story through a single image as a director would—by focusing the viewer’s eye not on Santa, the protagonist at the center of the narrative, and instead only implying his presence, Rockwell centers the painting on the true subject: the range of emotions among the children. Indeed, he is so masterful that the entire scene can be hypothesized from the small, succinct details he gives us: the holly pinned to the front boy’s shirt, gifts in the mother’s hand, and green floor punctuated with crimson red attire transport us to Christmastime in a department store. “Every picture is either the middle or the end of a story. You can also see the beginning even though it’s not there,” George Lucas elucidated. “You can see all the missing parts, and, of course, in filmmaking we strive for that. We strive to get images that convey visually a lot of information without spending a lot of time at it. Rockwell was a master of that, of telling a story in one frame.”ii i Viola Paradise, “An Audience of One,” Ladies’ Home Journal, December 1938, p. 21. ii George Lucas, quoted in Virginia M. Mecklenburg, Telling Stories: Normal Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, exh. cat., Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., 2010, p. 138.

Explore related art collections: Magazine Stories / Family / Children / $100,000 & Above / 1930s

See all original artwork by Norman Rockwell

ABOUT THE ARTIST

The pictures of Norman Perceval Rockwell (1894-1978) were recognized and enjoyed by almost everybody in America. The cover of The Saturday Evening Post was his showcase for over forty years, giving him an audience larger than that of any other artist in history. Over the years, he depicted there a unique collection of Americana, a series of vignettes of remarkable warmth and humor. In addition, he painted a great number of pictures for story illustrations, advertising campaigns, posters, calendars and books.

As his personal contribution during World War II, Rockwell painted the famous “Four Freedoms” posters, symbolizing for millions the war aims as described by President Franklin Roosevelt. One version of his “Freedom of Speech” painting is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rockwell left high school to attend classes at the National Academy of Design, and later studied under Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgeman at the Art Students League in New York. His two greatest influences were the completely opposite titans Howard Pyle and J.C Leyendecker.

His early illustrations were done for St. Nicholas magazine and other juvenile publications. He sold his first cover painting to the Post in 1916, and ended up doing over 300 more. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson sat for him for portraits, and he painted other world figures, including Nassar of Egypt and Nehru of India.

An important museum has been established in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he maintained his studio. Each year, tens of thousands visit the largest collection of his original paintings extant.