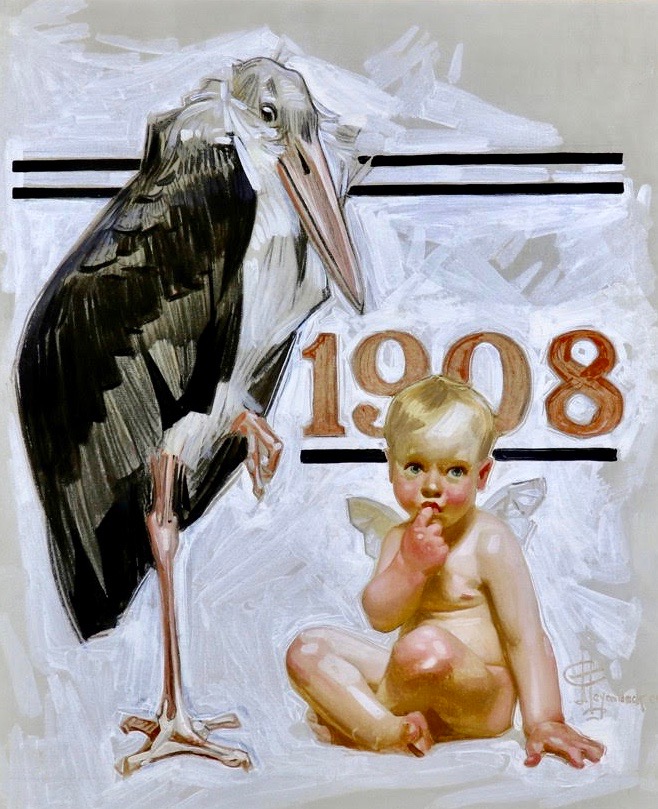

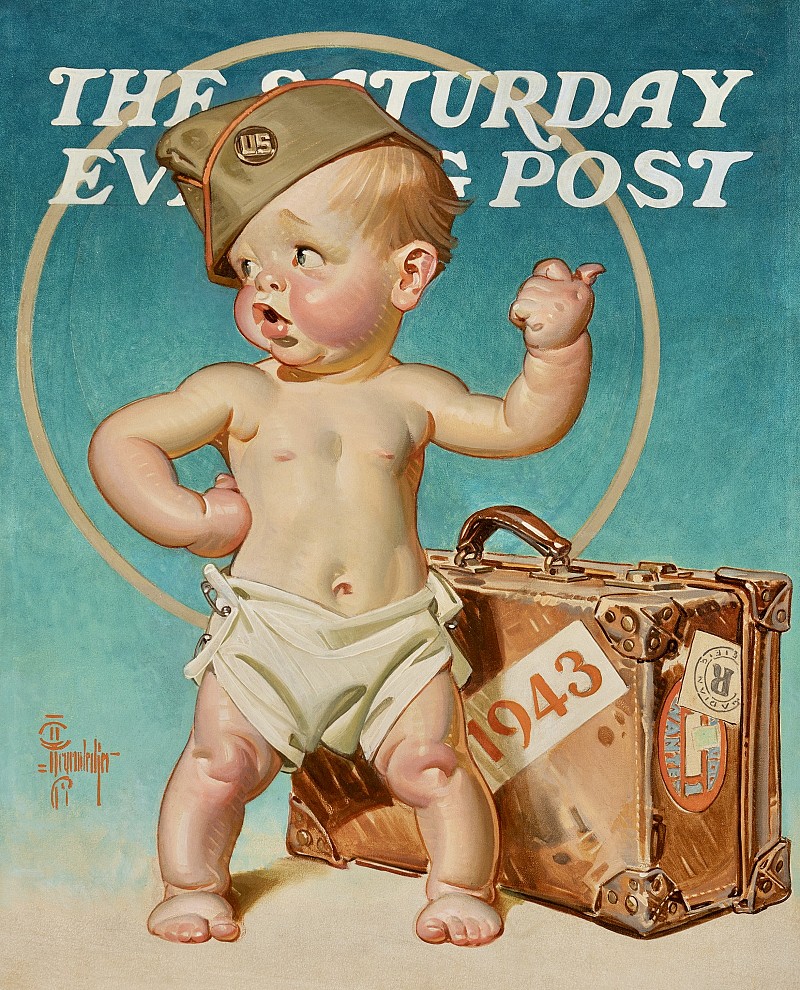

J.C. Leyendecker’s cherubs and babies graced the covers of 37 New Year’s issues of The Saturday Evening Post, ushering in each new year from 1907 to 1943. While the New Year’s Babies initially portrayed a childlike innocence, they soon began to offer commentary on the contemporary political and social issues facing the nation. This evolution of the New Year’s Baby is evident when comparing the baby’s second cover appearance on the December 25, 1907 issue, passively seated next to a stork, alongside New Year’s Baby Hitching to War, which Leyendecker intended for the January 2, 1943 issue of the magazine and features a baby soldier in diapers heading off to to the battle front.

In Hitching to War, the baby’s confident stance is belied by his slightly apprehensive expression as he attempts to hitch a ride to the battle front. Fearing the image portrayed too much uncertainty and could come across as unsympathetic to worried mothers sending their sons into battle, the Curtis Publishing team rejected this image and requested a more optimistic vision of certain victory. The publisher accepted Leyendecker’s second proposal for the January 2, 1943 issue, which featured a baby fighting symbols of the Axis powers in World War II against a blood-red background. However, the artist still incorporated the mixed emotions of the baby, and by extension the American public, who remained uncertain of the war’s outcome. This published cover captured the fighting spirit and dramatic effect the Curtis team desired, but the prominent inclusion of symbols associated with fascism and Nazism certainly detracts from its visual appeal, making Hitching to War the more desirable image for collectors. While Hitching to War was unpublished, the replacement cover that Leyendecker provided would ultimately become the artist’s last New Year’s Baby cover for the magazine, and his overall final cover for The Saturday Evening Post.

J. C. Leyendecker. Happy Landing. Original AMOCO Advertisement, published 1945. (Study also available)

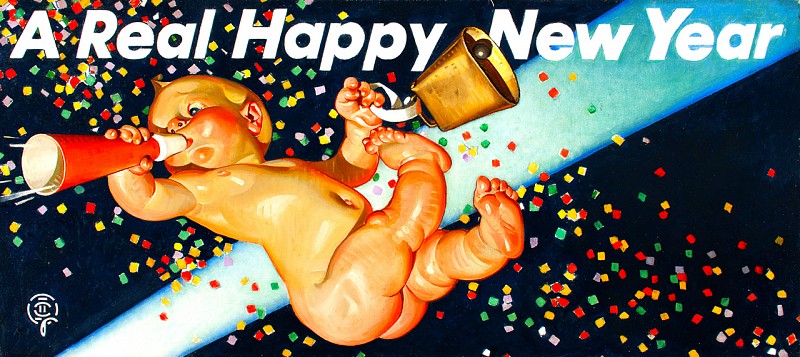

Following the success of Leyendecker’s Post covers, and capitalizing on the iconic status of the New Year’s Baby, the American Oil Company (AMOCO) hired the artist to create advertisements incorporating the babies throughout the 1940s. In Happy Landing, a helmeted New Year’s Baby parachutes from the sky as he releases a caged dove carrying an olive branch – a fitting and hopeful image that would resonate when it was first published in 1944, and later again in 1945, when the nation hoped each new year would bring an end to World War II. A Real Happy New Year, first used in AMOCO advertisements in 1946, features a joyous baby soaring on a field of confetti as he trumpets and rings in the new year, echoing the festive fervor felt by American citizens as they finally saw an end to the War in August of the previous year. AMOCO would later republish a variant of this image in 1952.

The New Years Baby instantly captured the hearts of the American public when it debuted on the cover of the December 29, 1906 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, and the beloved character continued to capture the spirit of the times throughout the first half of the 20th century. Today, the New Years Baby remains one of Leyendecker’s most lasting and recognizable contributions to American visual culture.